11.28.11 The Original Apple

When I was growing up, every 7 years my family lived in Spain. My father was a professor of Spanish literature, and he spent his sabbaticals doing research, writing and collecting the

Sephardic ballads that were his specialty. The year I turned 15 there, my sisters (5 and 7 years older than I) were already out of the house, so I was essentially an only child. I went everywhere with my parents, which meant a very diverse cultural life (opera, theater, dance, symphony, museums, galleries), lots of meals out and visits to some very fancy Madrid residences. Perhaps because we were in Europe—or maybe it had something to do with the almost exclusively adult company—the rules relaxed a bit and I was often allowed a glass of sherry, cointreau or vino tinto. This set the stage for expanding my appetite, too, and I tried many unknown delicacies: octopus, white asparagus, kidneys,

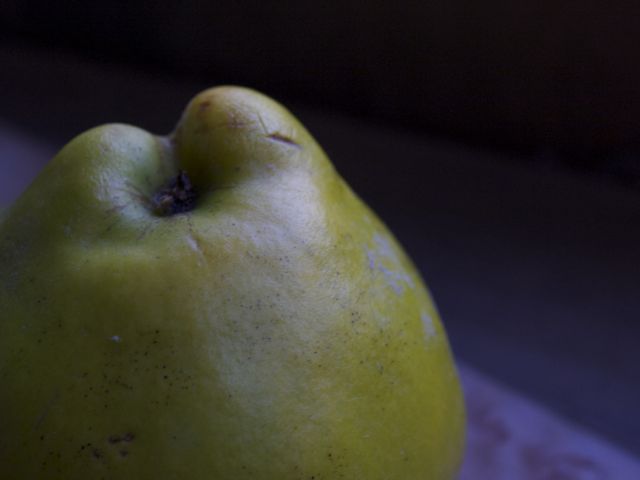

membrillo. The latter was a deep-amber-colored jelly that was often brought out with the cheese course (another novelty), a sticky, sweet confection to pair with the rich oily Manchego. At the time, I had never seen a quince, and it's a bit of a leap anyway from that fuzzy, essentially inedible fruit to this jammy nectar of the gods.

The quince is definitely not a convenience food and is thus rarely found in supermarkets. It's slightly mysterious, covered in a pale grey fuzz and smelling of spring flowers and exotic locales. Uncooked, it is hard, dry and mouth-puckeringly astringent. But once cooked, it softens and the flavor is unlike anything else: complex, floral, almost tropical. Quinces ripen in September and October, and can often be found at farmers markets through December. Look for bright golden yellow fruit with few traces of green and no soft spots.

The flesh of the quince oxidizes, turning brown quickly, but the heat coaxes from it a spectrum of colors ranging from pale rose to sunset orange. The final color depends on the varietal, on the ripeness and on how long you cook it. For paste, jams or jellies, it's best to leave the peels and even the cores as they add both flavor and pectin.

Although the book of Genesis does not name the specific type of fruit with which Eve tempted Adam, some ancient texts suggest it might have been a quince. Quinces pair well with apples, and are delicious simply poached in vanilla syrup.

After cooking the quinces down to a tender mush, you can put everything through a food mill like

this, or even puree it in a food processor. The nice thing about a food mill is that it forces the puree through a fine screen and removes any seeds or peel at the same time.

looks like applesauce, tastes like heaven

The puree is returned to the pot with some sugar and lemon juice and cooks and cooks and cooks until it's reduced to a thick russet-colored paste that is easily mounded up. Someone recently told me they made theirs with lime juice and cardamom, which made my mouth water. The recipe I used in Alice Waters' invaluable

Chez Panisse Fruit gave a cooking time of 45 minutes, but mine needed more than twice that before it would set up properly. This is one place where you simply have to use your own judgment, but I think it would be really hard to overcook it.

a glistening slab of goodness

spread the paste in a parchment-lined pan to dry

The drying process was a bit disconcerting. My paste certainly firmed up right away, and after drying it overnight, I sliced it into jewel-like cubes.

The trouble is, it was quite sticky. Weeping, in fact; meaning it was exuding a clear syrup. I rolled it in granulated sugar, which is how they serve the pâtes de fruit (fruit pastes) at Épicerie Boulud (go just for a piece of the passionfruit one), but the next day they had absorbed all the sugar and gone back to weeping. Hmmm... I left them out another day or so, then wiped them down with a paper towel and stacked them in a tupperware to keep in the fridge.

They are absolutely delicious simply eaten on their own, or paired with a ricotta salata or sharp pecorino.

In Morocco and the Middle East, quinces are often cooked with meat. Chez Panisse Fruit also includes a recipe for quinces with lamb, which is another wonderful pairing. This is a very easy dish to make and the North African spices go nicely with basmati rice or couscous.

The Chez Panisse recipe calls for cubed lamb shoulder but I used shanks and it came out perfectly. If you can get your hands on some quinces, I recommend you use them in both sweet and savory preparations so you can truly appreciate their range of flavors. And maybe keep a few in a bowl to perfume your livingroom over the holidays.

Quince Paste (aka Membrillo)

from Chez Panisse Fruit

makes about 80 1" square pieces

-

— 2 cups sugar, plus more for coating the pieces

-

— 3 cups water

-

— 3 pounds quinces, peeled, cored & diced

-

— juice of 1 lemon

Wash the quinces and wipe off any clinging fuzz. Cut them in quarters, remove the woody core and cut the quarters into roughly 1-inch pieces.

Put the quinces in a 4-quart pot, add the water and bring to a boil, cover, and steam over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until the fruit is soft, about 20 minutes. When the fruit is completely tender and has started to break down, pass the mixture through a food mill or sieve.

Return the puree to the pot, add the sugar and cook over low heat, stirring constantly for about 45 minutes (or much longer). The mixture will cook into a paste, bubbling thickly; when it’s done, it should be thick enough to mound up, but still pourable. If the mixture starts to burn in the pan before it has completely thickened, turn off the heat and let it rest for a few minutes; the part sticking to the bottom will release when you start stirring again. When the mixture reaches the right consistency, stir in the lemon juice and remove from the heat.

Line a shallow pan measuring at least 8x10 with parchment paper. Lightly oil the paper with vegetable oil or almond oil. Pour the paste onto the paper-lined pan, spreading it into an 8x10” rectangle, about ¼” thick. When it has cooled completely, invert the sheet of paste onto another sheet of parchment. Carefully peel off the upper, oiled sheet.

Let the paste dry uncovered overnight. If it is not firm enough to cut at this point, try drying it out for an hour or so in a low oven (around 150º). Once the paste is cool and firm, cut into 1” squares and toss them in sugar. Store uncovered in a dry place. When the paste is dry to the touch, it can be stored in an airtight container for as long as a year. The paste can also be kept whole, wrapped in parchment.

FYI, I am storing mine in the fridge. Someone told me you can also layer bay leaves between the pieces.

Download Recipe

Download Recipe

Lamb Tagine with Quinces

from Chez Panisse Fruit

serves 4

-

— 2 pounds quinces

-

— 2 tablespoons honey

-

— 1/2 teaspoon saffron, crushed

-

— 1 cinnamon stick

-

— 1 heaping teaspoon grated fresh ginger, or 1/2 tsp ground ginger

-

— 3 tablespoons unsalted butter

-

— 2 onions, peeled and grated

-

— olive oil

-

— salt & pepper

-

— 3 pounds boned lamb shoulder, cut into 2" cubes

-

— juice of 1/2 lemon

Trim off and discard excess surface fat from the lamb. Season the meat with salt and pepper. Cover the bottom of a heavy stew pot with oil, heat, add the meat, and brown lightly on all sides over medium-high heat. Do this in batches, if necessary, to avoid crowding. When the meat is browned, reduce the heat and pour off the oil. Add the onions, butter, cinnamon stick, ginger, saffron, and 1 teaspoon salt and cook for about 5 minutes, stirring and scraping up any brown bits from the bottom of the pan. Pour in enough water to just cover the meat and cook, covered, at a gentle simmer until the meat is tender, about 1½ hours.

While the lamb is cooking, wash the quinces, rub off any clinging fuzz, cut each quince into 8 wedges, and core them. Do not peel: the peel contributes texture and flavour to the stew. Place the wedges in lightly acidulated water to prevent them from browning. When the lamb is tender, taste the stew for saltiness and adjust as needed. Add the quinces, honey, and lemon juice and simmer for another 15-30 minutes, until the quince wedges are tender but not falling apart.

Download Recipe

Download Recipe

Download Recipe

Download Recipe

Download Recipe

Download Recipe

5 Comments