7.22.10 Fielding Questions

roger tory peterson and a young osprey photo by alfred eisenstaedt

I had my first guest-post on a kindred spirit's blog this week. The visionary Peter Buchanan-Smith honored me with a feature on his fascinating blog, Best Made Projects. We share an interest in the natural world, so when he asked me to review a field guide, I chose one by the naturalist and early environmentalist Roger Tory Peterson (seen above holding a movie camera mounted on a gun stock). Peter has kindly allowed me to re-post my review in its entirety here.FIELDING QUESTIONS: A Review of Roger Tory Peterson Field Guides - Eastern ForestsReturning home to Sullivan County from the stinky summer streets of New York City brings a surge of relief and gratitude: the cool night air filled with the rustle of leaves and the throbbing drone of cicadas is a tonic. The woods I now call home are not the same as those I grew up with in the Santa Cruz mountains of California. Fog-shrouded sequoias and wild surf are here replaced with blazing summers and snowy winters among the hawthorn, hickory, maple and pine. The Steller’s jay of my youth is now the equally brazen blue jay of my mid-life. The fence around our small property does little to keep out all the critters that also live here, and long rambles on our kind neighbor’s thousand acres have led to countless discoveries, animal, mineral and botanical.

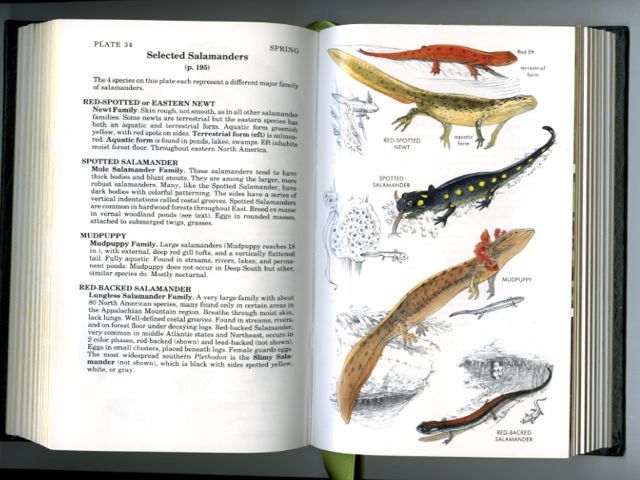

How then to begin to understand all these natural wonders? Each season brings uniquely intriguing sights and sounds, its own miraculous unfoldings. Where to turn to identify this orange amphibian, that proliferating fern, the eerie sound of that night creature?

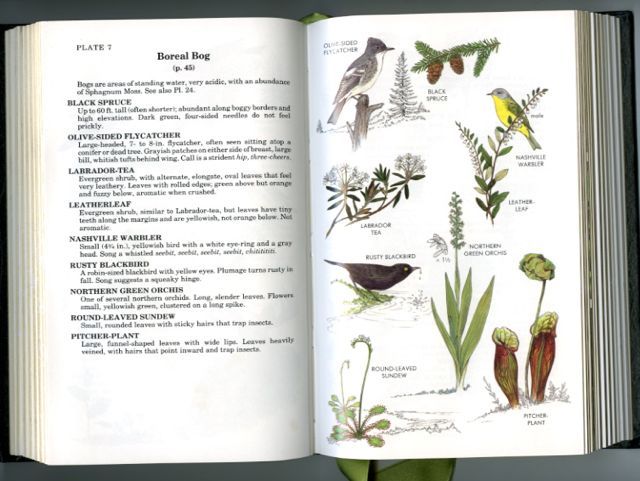

There is no more reliable and exhaustive source than Roger Tory Peterson (1908–1996). An American naturalist, ornithologist, artist and educator, he was one of the founding inspirations for the 20th-century environmental movement. No one of the past century has done more to promote an interest in living creatures. In 1934, he published the first modern field guide, his seminal Guide to the Birds. It sold out its first printing of 2‚000 copies in one week, and went through 5 subsequent editions. His detailed paintings and simplified method of identifying birds helped the layman become familiar with species through their easily observed “field marks,” rather than by the old “bird in the hand” method, thus replacing the shotgun with binoculars as the birder’s instrument of choice. Soon, his techniques were applied to all manner of flora and fauna.My green leather-bound, gilt-edged Roger Tory Peterson Field Guides Eastern Forests - North America (written by John C. Kricher, illustrated by Gordon Morrison and edited by the master himself) is a boon companion through all seasons. As the winter snows melted this year, I opened my book to “Patterns of Spring,” and headed into the forest to the vernal pools where spotted salamanders lay their jelly-like egg masses. I discovered that the small red efts crawling on the woodland floor on early summer mornings were in their interim terrestrial stage—an adaptation that helps them disperse—and would have an unpleasant “peppery” taste designed to repel predators. I returned to the book to positively identify what turned out to be yellow-bellied sapsuckers drilling away at our old lichen-covered maple, and to learn more about the wily woodchuck that has attacked our vegetable garden two years running.The first chapter acknowledges that “everyone begins to use a field guide by thumbing through the pages and looking at the plates of illustrations,” and, indeed, this 1988 edition has beautiful visuals that do justice to their subjects. But what’s genius about this particular field guide is that it places emphasis on the way plants and animals interact together, so you really gain an understanding of what a habitat entails. You learn the differences between a Boreal Bog (a wet, mossy place) and a Northern Hardwood Forest (full of Sugar Maple, White Pine and Eastern Hemlock) in terms of who lives there and what they eat.

Why is this good? Why do male juncos winter farther north than females? Why do some spider webs have thick zigzag strands? Why don’t herbivores eat all the leaves? Why ask why? For the answers to these and other pressing questions on the natural world, I refer you directly to Roger Tory Peterson Field Guides Eastern Forests - North America, which is laden with “Observations and Explanations,” and from whence came this illuminating statement: “Why-type questions are ultimate-type questions. They identify the most interesting aspects of natural history, those of adaptation and survival. The answers to ultimate-type questions reveal the actual fabric that holds nature together. Being able to ask and answer ultimate questions about natural history adds a new and powerful dimension to your understanding of nature.”

0 Comments